Migration Stories: Michal Towarnicki, Displaced Person

Posted on 16th Sep 2025 by Helen Kavanagh

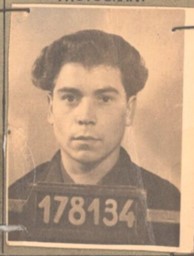

‘I don’t know much about Michal. Only that when Germany invaded Poland, he was taken prisoner and made to work in the German coal mines... for six months without being allowed up.’ So begins the handwritten note I found in the Michal Towarnicki collection – a bundle of 14 official documents from 1945 to 1987, that tell the story of a Polish-Ukrainian labourer who settled in the Wigan borough.

It is not just the story of one man – it is the story of the post-war problem of displaced persons – and how, over several years, it was resolved.

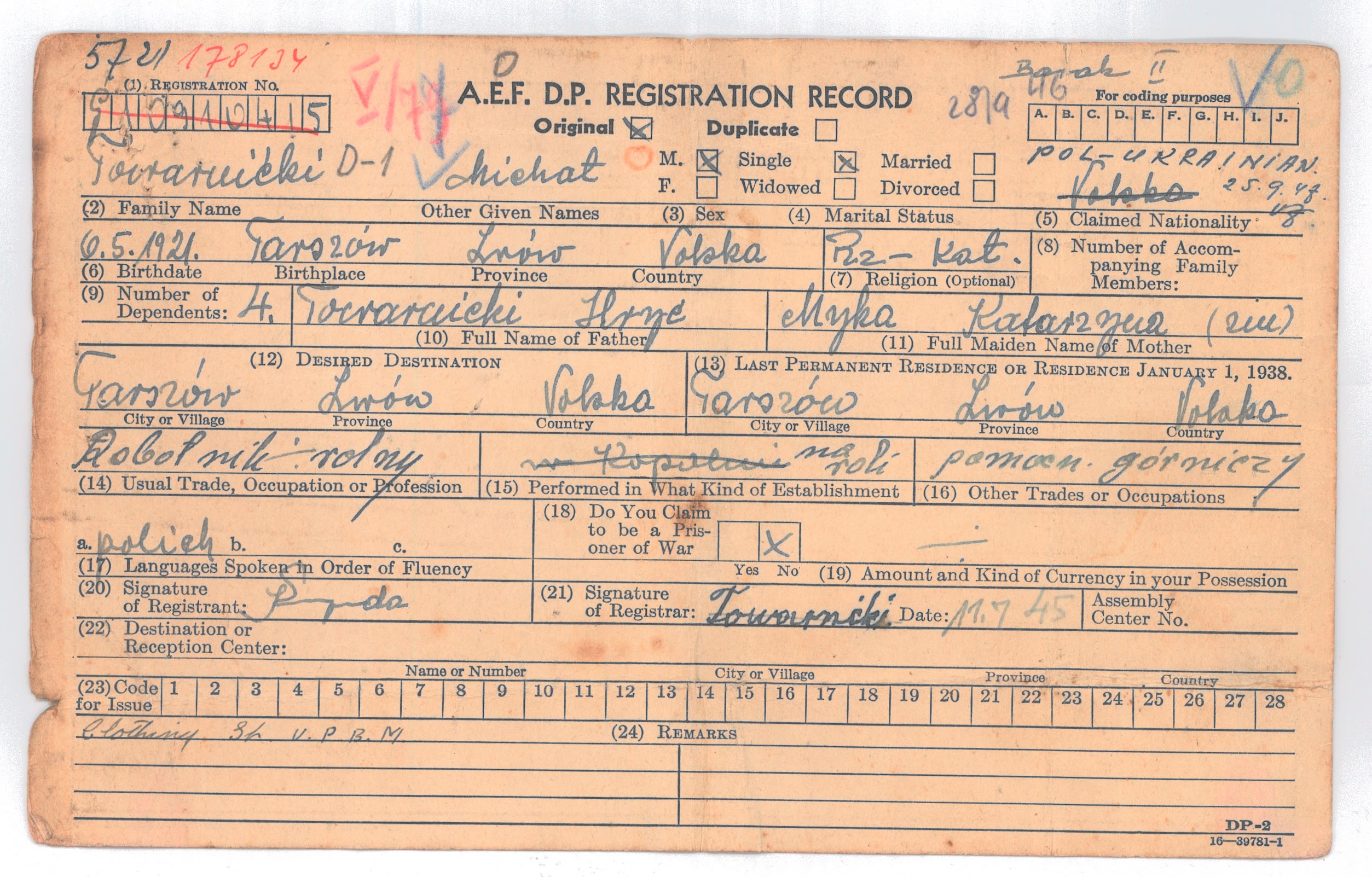

‘Displaced persons’ or ‘DPs’ were defined as all non-German civilians who had been deported by the Nazis or who, for some other reason related to the war, found themselves outside of their home countries when it ended. When the allies liberated Germany, they encountered between 10 and 12 million DPs. Michal was one and was registered as such in the British Zone on 17 July 1945.  Among many details, his registration card reveals he was 24 at the time of liberation, did not consider himself a Prisoner of War, and wished to return to his stated birthplace: Gorzów, Poland. This return was not to be, and on 11th November 1947, he left Osnabrück DP camp for the UK, after a lengthy screening process.

Among many details, his registration card reveals he was 24 at the time of liberation, did not consider himself a Prisoner of War, and wished to return to his stated birthplace: Gorzów, Poland. This return was not to be, and on 11th November 1947, he left Osnabrück DP camp for the UK, after a lengthy screening process.

This change of heart is possibly due to the fact his home country was now in the Soviets’ sphere of power. Arolsen archives writes that many ‘Polish, Baltic and Ukrainian DPs... did not want to live under Soviet rule and feared the repressions that potentially faced them in the Soviet Union. These fears were shared not only by those who had actually fought on the side of the Germans or who had supported the occupiers, but also by former forced labourers who would have been accused of being collaborators on account of their “work for the enemy.”’

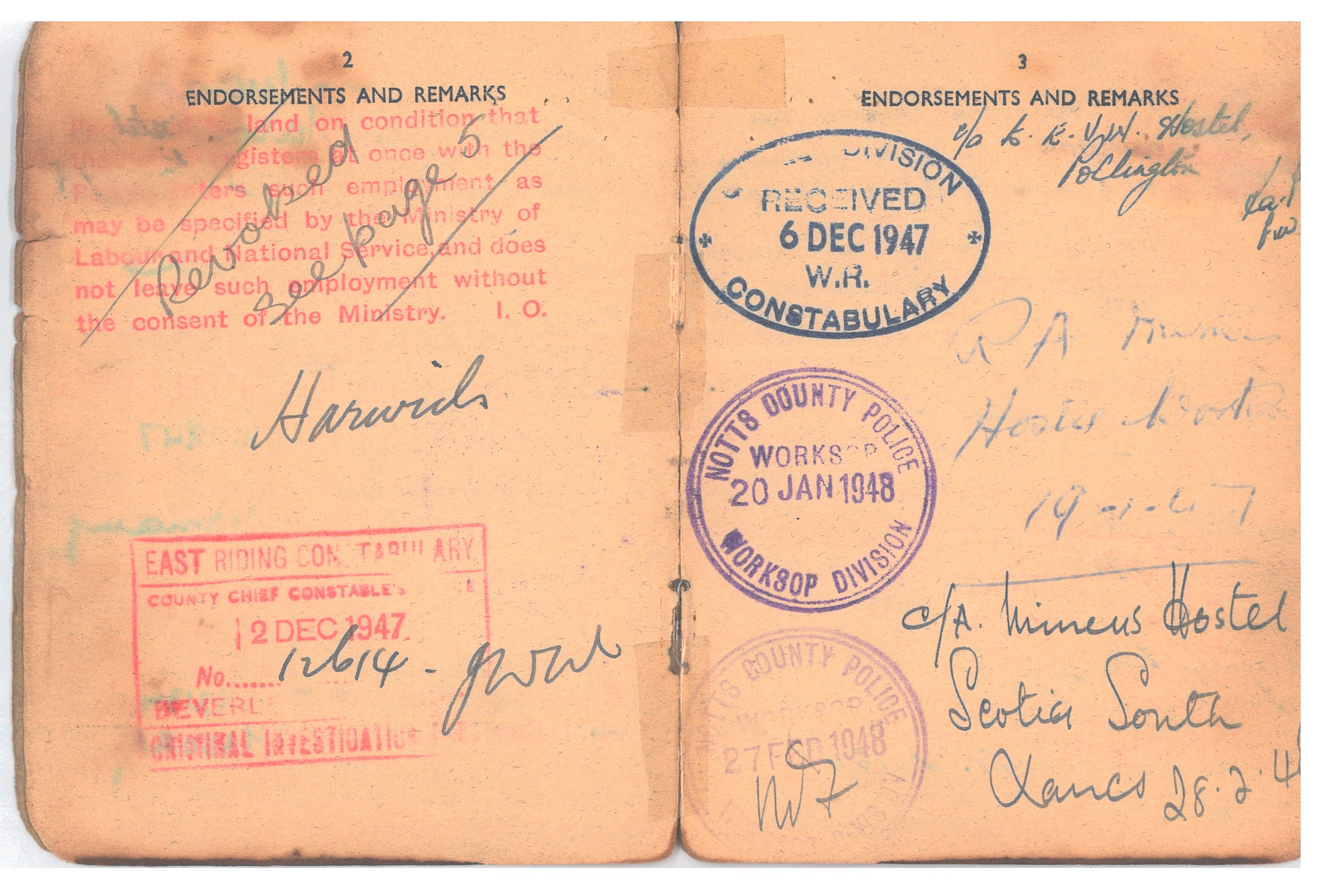

Despite these fears, the Allies continued to push ‘repatriation’ as the best option, until July 1947 when the International Refugee Organisation took responsibility for remaining DPs and introduced emigration a viable alternative. A few months later Michal arrived in the UK and made the European Voluntary Workers Camp in Yorkshire his first address.

Within four months he had found employment as a trainee miner at Parsonage Colliery in Leigh – a town that was to become his permanent home.

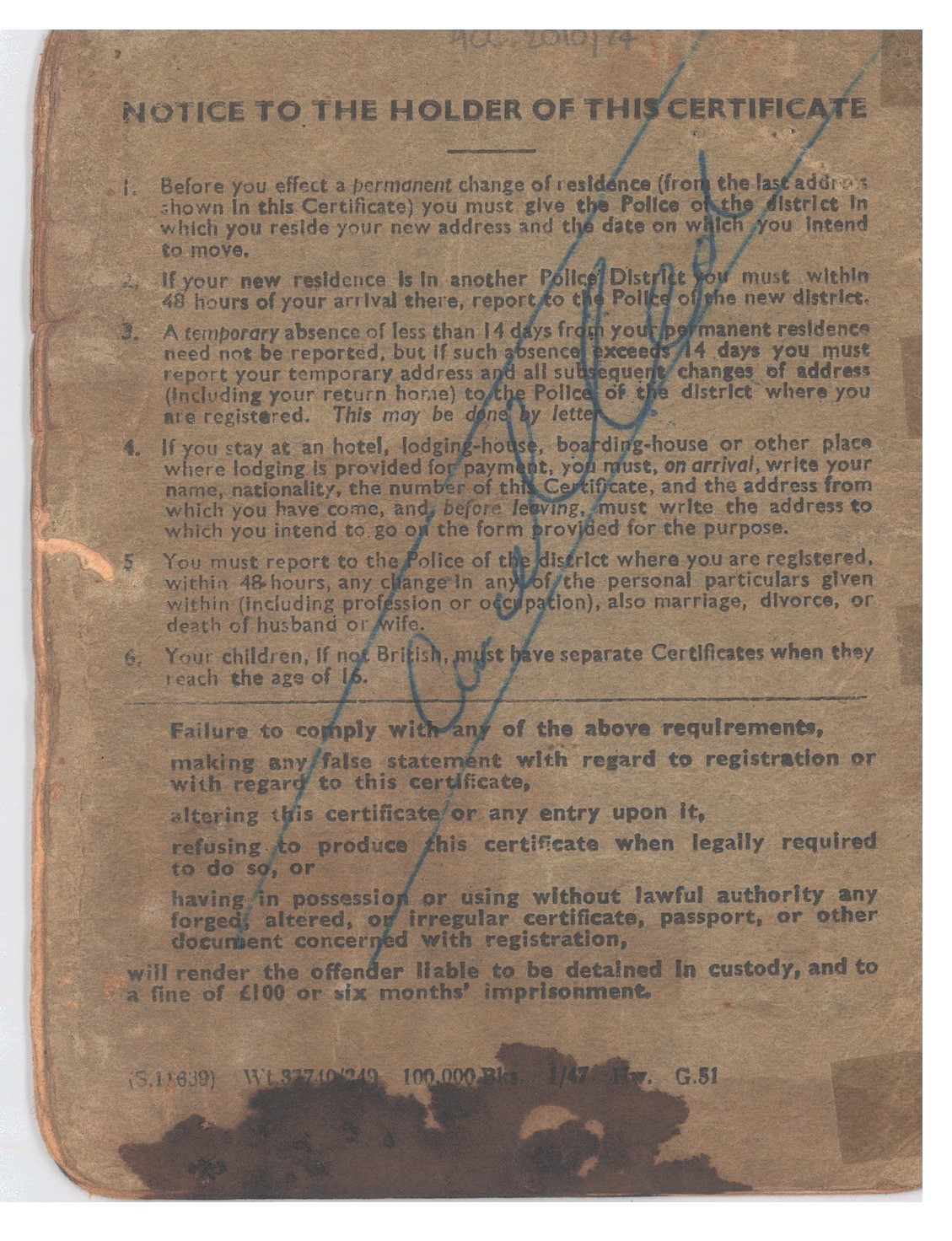

His life as an ‘alien’, throughout the 40s and 50s, was heavily constrained. His documents set out the rules of his tenure: he must report every new address to the police within 48 hours of arriving. He must report every change of employment to the Ministry of Labour - and was cautioned once by police for not doing so.

But later documents paint a picture of a man who has proved himself, through decades of hard work, and earned a modicum of trust from the British state in return. His 1969-70 Leigh Labour Club membership book doesn’t contain a mugshot, or list his distinguishing features – it merely tells us he had paid his subscription in full for the period. Pedestrian details like this reveal a settled man who was part of the community, enjoying a less turbulent period of history.

Michal died in 2002, aged 81. A handwritten note tells us that he is buried in Leigh Cemetery, with no headstone to mark his resting place. This fact seems to make the personal effects that survive him even more significant, as his only known memorial.

By Helen Raymond